Modern dining philosophers

How would one solve the dining philosophers problem at the end of 2018? It’s been 53 years since Dijkstra originally formulated the problem. Are we still using locks to solve it? Do we properly avoid deadlocks and starvation?

The vast majority of implementations I found doing an Internet search revealed to me that we are using mutexes or semaphores for it. But we mentioned previously that this is a bad approach; we should use tasks instead.

In this blog post, we give several solutions to the dining philosophers problem, each with some pros and cons. But, more importantly, we walk the reader through the most important aspects of using tasks to solve concurrency problems.

Instead of reaching for our higher-level frameworks, we opted to keep the level of abstractions as close as possible to raw tasks. This way, we hope to guide the reader to understand more about the essence of task-based programming. Our aim is to make the reader comprehend the machinery of composing tasks; those skills should be highly valuable.

The problem to be solved

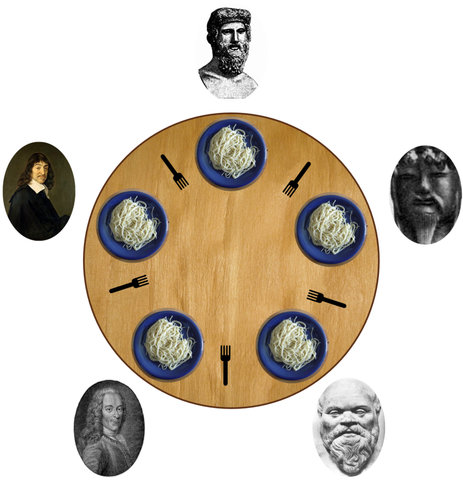

We have N philosophers dining at a round table (the original problem stated 5 philosophers, but let’s generalize). Each philosopher has a bowl of spaghetti in front of him. A fork is placed between each pair of adjacent philosophers. As a consequence, each philosopher has a fork on his left and on his right side.

Each philosopher will alternatively eat and think. Eating requires a philosopher to pick up both forks (from his left and right side). One fork cannot be used simultaneously by two philosophers; this means that when a philosopher eats, the adjacent philosophers must think. After eating, each philosopher must put the forks down, so that they can be available to other philosophers (including self). If a philosopher tries to eat and has the fork taken, it must go back to thinking.

The problem is to design a concurrent algorithm that will make the philosophers alternate eating and thinking, following the above constraints, without deadlocking, and without starving.

There are two main pitfalls to be avoided when designing a solution to this problem: deadlock and starvation.

A deadlock can occur, for example, if each philosopher will pick up the left fork, and cannot pick the right fork (as the philosopher on his right already picked it), and the algorithm requires a philosopher to wait indefinitely until the fork can be picked up.

Starvation can occur, for example, if a philosopher finds at least one fork busy each time he wants to eat.

The problem is often invoked as an example of mutual exclusion: we have a set of resources that need to be shared between multiple actors. The typical approach to this is to add mutexes or semaphores for solving the problem.

For our study, we particularize the problem in the following ways:

- after eating K times, the philosophers will leave the table – we want to ensure that our program terminates

- a philosopher always starts thinking when joining the dinner

- for reporting purposes, we distinguish between thinking after successful eating and thinking after a failure to eat

None of this will essentially change the core of the problem; just makes it easier for us to describe what we are doing.

Thinking tasks

Let’s first approach the problem by thinking in terms of tasks. At the first approximation, for each philosopher, we can have 3 types of tasks—eat, think and leave—, and we have constraints between the eat tasks.

For 3 philosophers, the chain of tasks would look something like:

The think tasks don’t need any special synchronization; they can run in parallel with any other tasks. Same for the leave tasks. The eat tasks, however, have synchronization conditions, based on the forks near each philosopher. We illustrated this fact in our diagram by writing what forks each eat task needs (between forks f0, f1 and f2).

This diagram provides a good approximation of the problem, but it leaves one important detail out: what happens if a philosopher cannot pick up the forks to start eating? It needs to fall back to thinking some more. And we didn’t properly account for that in our diagram.

Let us be more precise, and this time create a pseudo state diagram with tasks that a philosopher is having, encoding the possible transitions.

After thinking and before eating the philosopher needs to acquire the forks. There needs to be some logic corresponding to this activity, and we’ve depicted it in our diagram with a rounded yellow square. If the forks were successfully acquired, we can enqueue the eating task. Otherwise, we need to remain in the thinking state. For demonstration purposes, we make a distinction here between a regular thinking task and a hungry thinking task; we might as well have encoded them with a single task.

After eating, we need to release the forks; again a rounded yellow box. If the philosopher has been eating the required number of times, we enqueue the leaving task, and the philosopher leaves the party.

As one may expect, the important part of solving this problem corresponds to the two rounded yellow boxes. These are the only nodes that may have different outcomes and may require more logic.

But, before showing how we might solve the problem, we make a short digression and introduce all our tasking constructs.

Tip

Always start a concurrency problem by trying to draw (at least at a higher level) the tasks involved.

The tasks framework

In a problem concerning philosophers, it makes sense for us to aim at understanding the essence of things. Instead of using a higher level framework for solving the problems (futures, continuations, task flows, etc.), we aim to use low-level tasks as much as possible. We use this approach, as we are aiming at two things:

- instructs the reader how to think in terms of tasks

- show that tasks are a good concurrency primitive, that can be used to solve a large variety of problems

Here are the only declarations that we are using for solving the problems with tasks:

using Task = std::function<void()>;

class TaskExecutor {

public:

virtual ~TaskExecutor() {}

virtual void enqueue(Task t) = 0;

};

using TaskExecutorPtr = std::shared_ptr<TaskExecutor>;

class GlobalTaskExecutor : public TaskExecutor {

public:

GlobalTaskExecutor();

void enqueue(Task t) override;

};

class TaskSerializer : public TaskExecutor {

public:

TaskSerializer(TaskExecutorPtr executor);

void enqueue(Task t) override;

private:

//! The base executor we are using for executing the tasks passed to the serializer

TaskExecutorPtr baseExecutor_;

//! Queue of tasks that are not yet in execution

tbb::concurrent_queue<Task> standbyTasks_;

//! Indicates the number of tasks in the standby queue

tbb::atomic<int> count_{0};

//! Enqueues for execution the first task in our standby queue

void enqueueFirst();

//! Called when we finished executing one task, to continue with other tasks

void onTaskDone();

};And here is the implementation of these classes:

//! Wrapper to transform our Task into a TBB task

struct TaskWrapper : tbb::task {

Task ftor_;

TaskWrapper(Task t)

: ftor_(std::move(t)) {}

tbb::task* execute() {

ftor_();

return nullptr;

}

};

GlobalTaskExecutor::GlobalTaskExecutor() {}

void GlobalTaskExecutor::enqueue(Task t) {

auto& tbbTask = *new (tbb::task::allocate_root()) TaskWrapper(std::move(t));

tbb::task::enqueue(tbbTask);

}

TaskSerializer::TaskSerializer(TaskExecutorPtr executor)

: baseExecutor_(std::move(executor)) {}

void TaskSerializer::enqueue(Task t) {

// Add the task to our standby queue

standbyTasks_.emplace(std::move(t));

// If this the first task in our standby queue, start executing it

if (++count_ == 1)

enqueueFirst();

}

void TaskSerializer::enqueueFirst() {

// Get the task to execute

Task toExecute;

bool res = standbyTasks_.try_pop(toExecute);

assert(res);

// Enqueue the task

baseExecutor_->enqueue([this, t = std::move(toExecute)] {

// Execute current task

t();

// Check for continuation

this->onTaskDone();

});

}

void TaskSerializer::onTaskDone() {

// If we still have tasks in our standby queue, enqueue the first one.

// One at a time.

if (--count_ != 0)

enqueueFirst();

}This is it. That’s the only framework implementation needed to start solving complex concurrency problems using tasks (well, dining philosophers is not exactly a complex problem, but still…).

We chose to use Intel’s Threading Building Blocks library because it makes it easier for us to deal with tasks. But we might as well implement our abstractions on top of pure C++11 std::async feature (I wouldn’t necessarily recommend that, but let’s leave that discussion to another post).

Looking at the implementation, things are relatively straightforward:

- in its simplest form, a task is a function with no parameters that doesn’t return anything

- the GlobalTaskExecutor will just enqueue a task to be executed in the global task execution system

- one can enqueue multiple tasks in parallel, and most likely, these tasks will be executed in parallel

- the GlobalTaskExecutor::enqueue does not block waiting for the task to be executed

- the task serializer ensures that only one task passed to it will be executed at a given time

- to achieve this it maintains a queue of tasks

- new tasks go to the back of the queue

- while the queue is not empty, extract one task from the queue and enqueue it in the underlying task executor

- after each task execution is complete, we call

onTaskDoneto continue the execution - if there are still tasks in the queue, start the first one from the queue

- note the use of a lambda expression when enqueueing task in the serializer

- it is very useful for binding parameters to a function call

- also very useful to add a continuation to an existing task

- in our case, we want to call

onTaskDoneto enqueue the next task, as soon as the current task finishes executing

Pattern

One can use lambda expressions to bind parameters to functions and transform them into zero-parameter functions that can be used as tasks.

The philosophers

Let’s approach now the dining philosophers problem by starting to look at the Philosopher abstraction. We modeled the essential parts of the philosopher behavior but did not directly embed the dining protocol inside it. Instead, we keep the Philosopher class open to change and use a PhilosopherProtocol class to implement the details of the protocol (open-closed principle).

class Philosopher {

public:

Philosopher(const char* name)

: name_(name)

, eventLog_(name) {}

//! Called when the philosopher joins the dinner.

//! It follows the protocol to consume the given number of meals.

void start(std::unique_ptr<PhilosopherProtocol> protocol, int numMeals) {

mealsRemaining_ = numMeals;

doneDining_ = false;

protocol_ = std::move(protocol);

//! Describe ourselves to the protocol, and start dining

auto eatTask = [this] { this->doEat(); };

auto eatFailureTask = [this] { this->doEatFailure(); };

auto thinkTask = [this] { this->doThink(); };

auto leaveTask = [this] { this->doLeave(); };

protocol_->startDining(eatTask, eatFailureTask, thinkTask, leaveTask);

}

//! Checks if the philosopher is done with the dinner

bool isDone() const { return doneDining_; }

//! Getter for the event log of the philosopher

//! WARNING: Not thread-safe!

const PhilosopherEventLog& eventLog() const { return eventLog_; }

private:

//! The body of the eating task for the philosopher

void doEat() {

eventLog_.startActivity(ActivityType::eat);

wait(randBetween(10, 50));

eventLog_.endActivity(ActivityType::eat);

// According to the protocol, announce the end of eating

bool leavingTable = mealsRemaining_ > 1;

protocol_->onEatingDone(--mealsRemaining_ == 0);

}

//! The body of the eating task for the philosopher

void doEatFailure() {

eventLog_.startActivity(ActivityType::eatFailure);

wait(randBetween(5, 10));

eventLog_.endActivity(ActivityType::eatFailure);

protocol_->onThinkingDone();

}

//! The body of the thinking task for the philosopher

void doThink() {

eventLog_.startActivity(ActivityType::think);

wait(randBetween(5, 30));

eventLog_.endActivity(ActivityType::think);

protocol_->onThinkingDone();

}

//! The body of the leaving task for the philosopher

void doLeave() {

eventLog_.startActivity(ActivityType::leave);

doneDining_ = true;

}

//! The name of the philosopher.

std::string name_;

//! The number of meals remaining for the philosopher as part of the dinner.

int mealsRemaining_{0};

//! True if the philosopher is done dining and left the table

tbb::atomic<bool> doneDining_{false};

//! The protocol to follow at the dinner.

std::unique_ptr<PhilosopherProtocol> protocol_;

//! The event log for this philosopher

PhilosopherEventLog eventLog_;

};Let’s analyze this abstraction, piece by piece.

First, let’s look at the data for a philosopher. We have a name (currently not used), we keep track of how many meals the philosopher still needs to have before leaving the table, we have a flag telling us that the philosopher is done dining, and then we have a PhilosopherProtocol object that the philosopher should follow, and finally an event log that we use for keeping track of the actions that the philosopher is doing.

The doneDining_ flag is an atomic flag as it is accessed from multiple threads: it’s set by the thread that executes the leave task, and it’s also read from the main thread that checks if all the philosophers left the table.

The start method is called whenever a philosopher joins the dining table. It will pass a protocol to the philosopher. This protocol is used to actually implement the concurrency part of the problem. The philosopher just registers himself to the protocol, describing the behavior for the following actions: eating, thinking while after failing to eat, regular thinking and leaving. Again, to be noted how we use a lambda expression to bind the this parameter and form tasks that take no parameters.

The main thread will constantly call the isDone method to check when all philosophers left. The eventLog method is called after the philosopher left the table, to get the log of events associated with the philosopher, and do a pretty-print of the philosopher’s activities. Because this will only be called when all the tasks are done, there is no need to ensure thread-safety of this method.

Finally, we have doEat, doEatFailure, doThink and doLeave as private methods. These implement the behavior corresponding to each philosopher. In our implementation, these actions will just log the start of the activity, wait for a while, then log the end of the activity. After each of the action, we call the protocol to continue the philosopher’s dinner protocol.

As one can see, this form of design separates that dining policy out of the Philosopher class. It allows us to implement multiple policies without changing this class. The PhilosopherProtocol interface looks like this:

struct PhilosopherProtocol {

virtual ~PhilosopherProtocol() {}

//! Called when a philosopher joins the dining table.

//! Describes the eating, thinking and leaving behavior of the philosopher.

virtual void startDining(Task eatTask, Task eatFailureTask, Task thinkTask, Task leaveTask) = 0;

//! Called when a philosopher is done eating.

//! The given flag indicates if the philosopher had all the meals and its leaving

virtual void onEatingDone(bool leavingTable) = 0;

//! Called when a philosopher is done thinking.

virtual void onThinkingDone() = 0;

};This should be self-explanatory.

If we create a number of different philosophers, with some dining protocol, we can obtain an output similar to this:

Socrates: tEEt...EEt..EEt...EEt..EEEt..EEEt.....EEt...EEEt...EEt...EEL

Plato: t..EEtt..EEt...EEt...EEtt.EEt......EEtt..EEt....EEEt..EEEt.EEEL

Aristotle: tEEt...EEt..EEt...EEt..EEEt......EEt...EEt..EEEt...EEt...EEL

Descartes: t..EEtt..EEt...EEt...EEtt....EEEt..EEtt..EEt....EEEt.EEEt...EEEL

Spinoza: tEEt...EEt..EEt...EEt.....EEt....EEt...EEt..EEEt...EEt....EEL

Kant: t..EEtt..EEt...EEt.....EEEt..EEtt..EEtt..EEt....EEEt..EEEt...EEEL

Schopenhauer: tEEt...EEt..EEt.....EEEt...EEt..EEEt...EEt..EEEt....EEt....EEL

Nietzsche: t..EEtt..EEt.....EEtt..EEEt..EEEt..EEtt..EEt.....EEEt...EEt....EEL

Wittgenstein: t......EEt....EEEt..EEEt...EEt..EEEt...EEt.....EEtt..EEtt..EEEt..EEL

Heidegger: tEEt.......EEtt..EEtt..EEEt..EEEt..EEtt....EEEt....EEt..EEt....EEL

Sartre: t...EEEt.EEt...EEt...EEt...EEt..EEEt....EEt.....EEEt.EEtt..EEELIn this output, we mark with E an eating task, with t a pure thinking task, with . a thinking task resulting after failing to eat and with L the leaving task.

Now, let’s implement the protocol.

Take 1: an incorrect version

To warm ourselves up, let’s implement a version of the protocol that does not consider any constraints related to fork availability:

class IncorrectPhilosopherProtocol : public PhilosopherProtocol {

public:

IncorrectPhilosopherProtocol(TaskExecutorPtr executor)

: executor_(executor) {}

void startDining(Task eatTask, Task eatFailureTask, Task thinkTask, Task leaveTask) final {

eatTask_ = std::move(eatTask);

eatFailureTask_ = std::move(eatFailureTask);

thinkTask_ = std::move(thinkTask);

leaveTask_ = std::move(leaveTask);

executor_->enqueue(thinkTask); // Start by thinking

}

void onEatingDone(bool leavingTable) final {

if (!leavingTable)

executor_->enqueue(thinkTask_);

else

executor_->enqueue(leaveTask_);

}

void onThinkingDone() final {

executor_->enqueue(eatTask_);

}

private:

//! The executor of the tasks

TaskExecutorPtr executor_;

//! The implementation of the actions that the philosopher does

Task eatTask_, eatFailureTask_, thinkTask_, leaveTask_;

};This is a very simple implementation of the protocol that will just chain tasks, and nothing else. There are however a few key takeaways from this simple protocol implementation.

Key observation 1. We can easily chain tasks together by hand; the trick is to add an enqueue at the end of each task. In this case, the following flow happens;

-

startDining()enqueues the first thinking task - at the end of the thinking task,

onThinkingDoneis called; this enqueues the eating task - at the end of the eating task,

onEatingDone(false)is called; this enqueues the thinking task - after 3 eating tasks, interleaved with thinking,

onEatingDone(true)is called; this enqueues the leaving task

This is actually a simple implementation of the tasks described in Figure 2, ignoring any constraints imposed by the availability of forks.

Key observation 2. We’ve actually implemented a TaskSerializer by hand. Although we didn’t use a TaskSerializer object, by how we do the enqueueing of tasks at the end of other tasks we essentially obtain serialization of tasks. This will guarantee that there will not be two tasks corresponding to a single philosopher executed in parallel.

Pattern

One can create chains of tasks by hand by adding logic to enqueue the next task at the end of each task. This pattern can be used to implement by hand any task graph (i.e., model any concurrency problem).

Using a waiter

Ok, now it’s time to look into solving the problem with forks contention. Forks are a resource that requires exclusive access: two philosophers cannot use the same fork at the same time. We need to serialize the access to the forks while preventing the philosophers to enter a deadlock state.

One simple way of solving this problem is to add a waiter: this is one actor that is responsible for distributing the forks among the philosophers (see arbitrator solution). Instead of philosophers picking up the forks by themselves, they request the forks to the waiter; if the forks are available, they will be handed to the philosopher. Similarly, when a philosopher finishes eating, it will pass the forks to the waiter (hopefully to clean them before making them available to the next philosopher).

The implementation of such a protocol looks the following way:

class Waiter {

public:

Waiter(int numSeats, TaskExecutorPtr executor)

: executor_(executor)

, serializer_(executor) {

// Arrange the forks on the table; they are not in use at this time

forksInUse_.resize(numSeats, false);

}

void requestForks(int philosopherIdx, Task onSuccess, Task onFailure) {

serializer_.enqueue([this, philosopherIdx,

s = std::move(onSuccess), f = std::move(onFailure)] {

this->doRequestForks(philosopherIdx, std::move(s), std::move(f));

});

}

void returnForks(int philosopherIdx) {

serializer_.enqueue([this, philosopherIdx] {

this->doReturnForks(philosopherIdx);

});

}

private:

//! Called when a philosopher requests the forks for eating.

//! If the forks are available, mark them as being in use and execute the onSucceess task.

//! If the forks are not available, execute the onFailure task.

//! This is always called under our serializer.

void doRequestForks(int philosopherIdx, Task onSuccess, Task onFailure) {

int numSeats = forksInUse_.size();

int idxLeft = philosopherIdx;

int idxRight = (philosopherIdx + 1) % numSeats;

if (!forksInUse_[idxLeft] && !forksInUse_[idxRight]) {

executor_->enqueue(std::move(onSuccess)); // enqueue asap

forksInUse_[idxLeft] = true;

forksInUse_[idxRight] = true;

} else {

executor_->enqueue(std::move(onFailure));

}

}

//! Called when a philosopher is done eating and returns the forks

void doReturnForks(int philosopherIdx) {

int numSeats = forksInUse_.size();

int idxLeft = philosopherIdx;

int idxRight = (philosopherIdx + 1) % numSeats;

assert(forksInUse_[idxLeft]);

assert(forksInUse_[idxRight]);

forksInUse_[idxLeft] = false;

forksInUse_[idxRight] = false;

}

//! The forks on the table, with flag indicating whether they are in use or not

std::vector<bool> forksInUse_;

//! The executor used to schedule tasks

TaskExecutorPtr executor_;

//! Serializer object used to ensure serialized accessed to the waiter

TaskSerializer serializer_;

};

class WaiterPhilosopherProtocol : public PhilosopherProtocol {

public:

WaiterPhilosopherProtocol(

int philosopherIdx, std::shared_ptr<Waiter> waiter, TaskExecutorPtr executor)

: philosopherIdx_(philosopherIdx)

, waiter_(waiter)

, executor_(executor) {}

void startDining(Task eatTask, Task eatFailureTask, Task thinkTask, Task leaveTask) final {

eatTask_ = std::move(eatTask);

eatFailureTask_ = std::move(eatFailureTask);

thinkTask_ = std::move(thinkTask);

leaveTask_ = std::move(leaveTask);

executor_->enqueue(thinkTask); // Start by thinking

}

void onEatingDone(bool leavingTable) final {

// Return the forks

waiter_->returnForks(philosopherIdx_);

// Next action for the philosopher

if (!leavingTable)

executor_->enqueue(thinkTask_);

else

executor_->enqueue(leaveTask_);

}

void onThinkingDone() final {

waiter_->requestForks(philosopherIdx_, eatTask_, eatFailureTask_);

}

private:

//! The index of the philosopher

int philosopherIdx_;

//! The waiter who is responsible for handling and receiving the forks

std::shared_ptr<Waiter> waiter_;

//! The executor of the tasks

TaskExecutorPtr executor_;

//! The implementation of the actions that the philosopher does

Task eatTask_, eatFailureTask_, thinkTask_, leaveTask_;

};The protocol implementation is still simple, as most of the work is done by the waiter. When thinking is done, it will request the waiter for the forks. Unlike the previous version, this operation can result in failure; therefore we have two possible continuations: the philosopher starts eating or the philosopher falls back to thinking as a result of an eating failure. The protocol just calls requestForks passing the two tasks to be executed as a continuation; the waiter is guaranteed to enqueue one of these tasks.

When the philosopher is done eating, the forks are returned to the waiter by calling the returnForks method. After that, the philosopher can enqueue the next task to be done: either thinking or leaving.

With this implementation, please note that the philosopher may start to think while the forks are being returned to the waiter. This reduces the latency for the philosopher, but adds another potential case to our problem; see below.

For this solution to work, there needs to be only one waiter that is shared amongst all protocol objects.

Now, let’s turn our attention to the Waiter class. It keeps track of all the forks in use inside an std::vector<bool> object. As philosophers may want to call the waiter from different threads, the waiter serializes the access to this data member by using a TaskSerializer. Imagine how this would work in real life: the waiter can be called in parallel by multiple persons, but it cannot interact with multiple people at once. Therefore he keeps track of who called him, and as soon as he is done with one person, it moves to accommodate the request of the next one. In order words, the actions of the waiter are serialized.

Using a TaskSerializer here would be somehow equivalent to using a mutex to protect the inner data of the waiter, with the main advantage that it will not block the callers.

Once this problem is solved, the actual logic inside the Waiter class is simple: whenever it is asked for forks, checks for availability and responds correspondingly (success or failure); whenever the forks are returned, it will mark the forks as not being used anymore.

Encapsulation of threading concerns

Probably the biggest advantage of using tasks inside the Waiter class is the encapsulation of inner threading logic. The fact that we are using a task serializer is not exposed to the outside world. We could have just as well used mutexes on inner tasks (abomination!).

If we would have just used mutexes without any tasks, the caller could observe the fact that the calls made to Waiter would block. It could change its implementation, and moreover, in certain circumstances, it might also lead to deadlocks.

What we gained by doing this is composability. I’m not sure how to properly emphasize the importance of composability. Composability is fundamental in software engineering. That is because the main approach of solving problems in computer science is decomposition, which needs composition to aggregate the smaller wins.

We can say that this simple class implements the active object pattern: the method execution is decoupled from the method invocation. In some sense, this is also similar to the actor model.

Pattern

One can hide the threading constraints from the outside world, by using an internal task serializer, and enqueueing all work to it. This proves really useful at decoupling concerns.

An interesting case

The way we constructed our waiter protocol, we can have a very interested: one philosopher is waiting on himself to release the forks.

We said that we wanted the philosopher to start thinking immediately after finishing to eat, in parallel with handling the forks to the waiter. That is good for latency (i.e., help the philosopher get to the thinking state faster). But, what happens if the waiter is busy for a long time?

The philosopher can finish up thinking, try to acquire the forks from the waiter, even before the waiter took the forks from him.

In our case, nothing bad happens. The philosopher will be just denied to eat and it will be back in the thinking state.

I wanted to briefly touch this case as we often encounter similar cases in practice. Each time we are doing things in parallel, we need to create a small indeterminism, which may lead to strange cases. We need to be fully prepared for such cases.

Fairness

This implementation lacks fairness. For example, it may lead to this case:

Socrates: tt.................................EEEEEEEtttttEEEtttEEEEEEEL

Plato: tttttt......EEtttEEEEEtt........EEL

Aristotle: ttEEEEEEEE t..EEtt......EEEEEEELHere, Socrates is denied to eat until both Plato and Aristotle leave the table. Poor Socrates, left starving…

Aristotle finished up the first thinking part and requests the forks. When Plato and Socrates first finish thinking they could not acquire the required forks from the waiter. Each time Socrates is done thinking and attempt to get the forks, the waiter will deny the request, and Socrates needs to think some more.

This may be attributed to Socrates’ luck, but the waiter is clearly unfair. If Socrates was requesting the forks earlier, why does the waiter give the forks to Plato and Aristotle? Probably because the waiter doesn’t have any memory of who requested the forks.

Adding fairness

To add fairness to the implementation and avoid starving, we will add memory to the waiter.

class WaiterFair {

public:

WaiterFair(int numSeats, TaskExecutorPtr executor)

: executor_(executor)

, serializer_(executor) {

// Arrange the forks on the table; they are not in use at this time

forksInUse_.resize(numSeats, false);

// The waiting queue is bounded by the number of seats

waitingQueue_.reserve(numSeats);

}

// ...

private:

void doRequestForks(int philosopherIdx, Task onSuccess, Task onFailure) {

int numSeats = forksInUse_.size();

int idxLeft = philosopherIdx;

int idxRight = (philosopherIdx + 1) % numSeats;

int leftPhId = (numSeats + philosopherIdx - 1) % numSeats;

int rightPhId = (philosopherIdx + 1) % numSeats;

bool canEat = !forksInUse_[idxLeft] && !forksInUse_[idxRight];

if ( canEat ) {

// The neighbors should not be in the waiting queue before this one

for ( int i=0; i<int(waitingQueue_.size()); i++) {

int phId = waitingQueue_[i];

if (phId == philosopherIdx) {

// We found ourselves in the list, before any of the neighbors.

// Remove ourselves from the waiting list and approve eating.

waitingQueue_.erase(waitingQueue_.begin() + i);

break;

}

else if (phId == leftPhId || phId == rightPhId) {

// A neighbor is before us in the waiting list. Deny the eating

canEat = false;

break;

}

}

}

if (canEat) {

// Mark the forks as being in use, and start eating

executor_->enqueue(std::move(onSuccess)); // enqueue asap

forksInUse_[idxLeft] = true;

forksInUse_[idxRight] = true;

} else {

executor_->enqueue(std::move(onFailure)); // enqueue asap

// Ensure that this philosopher is on the list; if it's not, add it

auto it = std::find(waitingQueue_.begin(), waitingQueue_.end(), philosopherIdx);

if (it == waitingQueue_.end())

waitingQueue_.push_back(philosopherIdx);

}

}

//! The forks on the table, with flag indicating whether they are in use or not

std::vector<bool> forksInUse_;

//! The eat requests that are failed, in order

std::vector<int> waitingQueue_;

//! The executor used to schedule tasks

TaskExecutorPtr executor_;

//! Serializer object used to ensure serialized accessed to the waiter

TaskSerializer serializer_;

};Essentially, the algorithm is the same, but we add the waitingQueue_ to maintain fairness. If a philosopher requests the forks, but a neighbor requested the forks before this one, the request will be denied. This way, the neighbor that requested the forks first will have priority.

The output of running the program would look like the following:

Socrates: tEEt.......EEEt...EEEt.....EEt...EEEt........EEEt....EEt....EE t..

Plato: t.......EEt....EEt.....EEtt...EEEt........EEt...EEtt......EEt...EE

Aristotle: t...EEEt...EEEt.....EEt....EEt........EEEt...EEEt......EE t..EEEt.

Descartes: tEEt....EEt.....EEtt....EEt.........EEt...EEt........EEt...EEt....

Spinoza: t...EEEt.....EEt......EEt.......EEEt..EEEt.......EEEt..EEtt.......

Kant: tEEt......EEt.....EEEt.......EEt....EEt......EEEt....EEt...... ...

Schopenhauer: t......EEt.....EEt.........EEt...EEt......EEt....EEEt......... EEt

Nietzsche: t...EEEt...EEEt.........EEt...EEt.....EEEt...EEEt...........EEtt..

Wittgenstein: tEEt.....EEt.........EEt...EEt.....EEt....EEt...........EEEt....EE

Heidegger: t......EEt........EEEt.EEtt.....EEEt...EEEt..........EEt....EE t..

Sartre: t..EEtt........EEt...EEt.....EEtt...EEt..........EEEt...EEEt.. EEtOne can see with the naked eye that the philosophers have some kind of a round-robin turn for eating.

On the other hand, what’s also visible from this output is that there are times in which the forks are not used by any of the philosophers. That is because once a philosopher announces its intention to eat, it will prevent the neighbor philosophers from eating again, while the philosopher is thinking.

Tip

Be careful when adding fairness to concurrent processes; it often leads to worse throughput performance.

Synchronization at the fork level

The solutions presented so far solve the problem decently, but they do not scale properly. The waiter is a bottleneck. There is a common resource that needs to be exclusively taken in order to properly implement the dining protocol.

Another approach for this problem is to treat the forks as the resources that need to be taken. Instead of adding a contention in a central place, we distribute the contention to the forks. There is no need to make all the philosophers wait when a fork is needed when only one neighbor philosopher is affected.

Here is the implementation:

class Fork {

public:

Fork(int forkIdx, TaskExecutorPtr executor)

: forkIdx_(forkIdx)

, serializer_(executor) {}

void request(int philosopherIdx, TaskExecutorPtr executor, Task onSuccess, Task onFailure) {

serializer_.enqueue([this, philosopherIdx, executor,

s = std::move(onSuccess), f = std::move(onFailure)] {

if (!inUse_ || philosopherIdx_ == philosopherIdx) {

inUse_ = true;

philosopherIdx_ = philosopherIdx;

executor->enqueue(s);

} else

executor->enqueue(f);

});

}

void release() {

serializer_.enqueue([this] { inUse_ = false; });

}

private:

//! The index of the fork

int forkIdx_;

//! Indicates if the fork is in used or not

bool inUse_{false};

//! The index of the philosopher using this fork; set only if inUse_

int philosopherIdx_{0};

//! The object used to serialize access to the fork

TaskSerializer serializer_;

};

using ForkPtr = std::shared_ptr<Fork>;

class ForkLevelPhilosopherProtocol : public PhilosopherProtocol {

public:

ForkLevelPhilosopherProtocol(

int philosopherIdx, ForkPtr leftFork, ForkPtr rightFork, TaskExecutorPtr executor)

: philosopherIdx_(philosopherIdx)

, serializer_(std::make_shared<TaskSerializer>(executor))

, executor_(executor) {

forks_[0] = leftFork;

forks_[1] = rightFork;

}

void startDining(Task eatTask, Task eatFailureTask, Task thinkTask, Task leaveTask) final {

eatTask_ = std::move(eatTask);

eatFailureTask_ = std::move(eatFailureTask);

thinkTask_ = std::move(thinkTask);

leaveTask_ = std::move(leaveTask);

forksTaken_[0] = false;

forksTaken_[1] = false;

forksResponses_ = 0;

executor_->enqueue(thinkTask); // Start by thinking

}

void onEatingDone(bool leavingTable) final {

// Return the forks

forks_[0]->release();

forks_[1]->release();

// Next action for the philosopher

if (!leavingTable)

executor_->enqueue(thinkTask_);

else

executor_->enqueue(leaveTask_);

}

void onThinkingDone() final {

forks_[0]->request(philosopherIdx_, serializer_,

[this] { onForkStatus(0, true); }, [this] { onForkStatus(0, false); });

forks_[1]->request(philosopherIdx_, serializer_,

[this] { onForkStatus(1, true); }, [this] { onForkStatus(1, false); });

}

private:

void onForkStatus(int forkIdx, bool isAcquired) {

// Store the fork status

forksTaken_[forkIdx] = isAcquired;

// Do we have response from both forks?

if (++forksResponses_ == 2) {

if (forksTaken_[0] && forksTaken_[1]) {

// Success

executor_->enqueue(eatTask_);

} else {

// Release the forks

if (forksTaken_[0]) forks_[0]->release();

if (forksTaken_[1]) forks_[1]->release();

// Philosopher just had an eating failure

executor_->enqueue(eatFailureTask_);

}

// Reset this for the next round of eat request

forksResponses_ = 0;

}

}

//! The index of the philosopher

int philosopherIdx_;

//! The forks near the philosopher

ForkPtr forks_[2];

//! Indicates which forks are taken

bool forksTaken_[2]{false, false};

//! The number of responses got from the forks

int forksResponses_{0};

//! The executor of the tasks

TaskExecutorPtr executor_;

//! Serializer used to process notifications from the forks

std::shared_ptr<TaskSerializer> serializer_;

//! The implementation of the actions that the philosopher does

Task eatTask_, eatFailureTask_, thinkTask_, leaveTask_;

};This is slightly more code, but not complicated at all. Nevertheless, we will explain it.

The first thing to notice is the implementation of the Fork class. It uses the same active object pattern for keeping the threading implementation hidden from the caller. We could have implemented the whole thing with an atomic, but it wouldn’t be that much fun ![]() .

.

Whenever a fork is in use, we also keep track of what philosopher is using it. If another philosopher requests the fork we deny it, but we accept if the same philosopher requests the fork. This prevents some edge cases as discussed above with the waiter solution.

The protocol now becomes slightly more evolved. Whenever a philosopher wants to eat, we request the corresponding forks. The response from both forks, whether is a success or a failure, would be sent through a task notification to the onForkStatus function. This will ensure that we have a response from both forks before start eating or thinking. If we have a reject from one fork, we must release the other fork. We do nothing more than just follow the possible scenarios; nothing fancy.

The part that is worth noting is the serializer_ object attached to the protocol. Since we are getting notifications in terms for tasks from both fork objects, we need to ensure that they do not run in parallel. That’s why we instruct the Fork objects to use a serializer when sending the notifications back. If we wouldn’t have the serializer, two notifications could be processed in parallel, and we would have a race condition inside the body of onForkStatus.

A pattern for notifications

Please look more closely to the way the ForkLevelPhilosopherProtocol objects know about the status of the two forks. They receive notifications from the two Fork objects.

But we don’t have any explicit abstractions for notifications. That is because we don’t need it. One can take the pair between a TaskExecutor and a Task to serve as a notification object. In our example, whenever the Fork object needs to send a notification to the protocol object, it will enqueue the given task on the appropriate executor. That’s it. Simple as daylight.

Notification pattern

One can use a pair between a `TaskExecutor` and a `Task` as a channel of sending notifications.

Fairness

The astute reader might have noticed that this implementation does not have fairness. Indeed, with the way we have set up our fork synchronization, we don’t have a memory of who requested the forks first. We can have the same case in which Socrates is denied to eat until both Plato and Aristotle finish dining.

But, beware, in this case, adding fairness is not that easy. If we would simply want to keep track of who requested the forks, we would simply reach a live-lock situation. Imagine that each philosopher requests the left fork first, then the right fork. No one will be able to acquire the right fork, as it was already promised to the philosopher on the right. From that point on, it is guaranteed that the forks will not be acquired by any of the philosophers; they would always go back to thinking, wake up to have their requests denied.

On correctness of the current solution

But wait, doesn’t the solution presented here suffer from a similar problem? Let’s imagine the following scenario:

- all philosophers stop thinking at the same time

- they all start by acquiring the left fork; they will all send a notification to the forks on their left to acquire them

- then, they all send a notification to acquire the right forks

- the forks will process the messages in order; all the “take left” requests will be fulfilled before the “take right” ones

- this will essentially deny all the philosophers the possibility of eating

- they all go back to thinking, they all wake up at the same time, and the cycle continues

This is true, but this is mostly a theoretical problem. In practice, because enqueueing and executing tasks have some timing randomness, the possibility of this happening once is extremely small; and it exponentially decreases as the time goes by. It’s enough to have one small randomness to change the order of the tasks to be executed for the whole live-lock chain to be broken.

If we want to fix this problem, we could easily swap the fork requesting for one single philosopher (i.e., the first philosopher requests the right fork first, then the left one). We leave this as an exercise to the reader.

Conclusions and a few other notes

In this blog post, we walked the reader through building several solutions for the dining philosophers problem. The intent was not to build up the best possible solution (fastest, easiest, etc.) but rather to explore the various aspects of working with tasks. We intentionally tried to keep the number of concurrency abstractions to the minimum and guide the reader through the essentials of using tasks.

We’ve shown how to build a simple task system, and how to use it to solve various problems. Along the way, we encountered several patterns that can appear while building concurrent applications (with tasks):

- how one can use lambda expressions to transform regular function calls into task objects

- how one can enqueue tasks by hand to create arbitrarily complex chains or graphs of tasks.

- an active object pattern in which we keep the concurrency concerns of a class isolated from the calling code; this pattern also helps in achieving composability with actors that are doing work in a multi-threaded environment

- a pattern for notifications between various actors using tasks

Hope that after this (relatively longer) post the reader has a better grip on using tasks to build solutions for concurrency problems.

The dining philosophers problem was just a pretext for our journey.

All the code can be found on Github: at https://github.com/lucteo/tasks_concurrency/tree/dining_philosophers

Keep truthing! Until the next task time.

Comments