Golden mean in software engineering

People often talk about modularity in software design, about conquering complexity, about reducing coupling and about decomposition. But often those discussions revolve around some concrete examples. Although this is generally a good thing, there is always the question of “does it also apply to my case?” We should also be looking at this from a more abstract way, to approach the essence of things.

While this blog post is far from an exposition of the essence of these things, it attempts to start an investigation in this direction. Even in its abstract form, it can be useful to draw some practical conclusions. But more importantly, it is a starting point for having more detailed discussions on taming complexity.

We will approach the problem of organizing complexity by tackling a somehow simpler problem: how can we group software entities in such a way that we better manage complexity. This is somehow a different take on the old question of how to decompose software. But instead of providing criteria of dividing into modules based on meaning, we are more interested in a more abstract complexity. We aim at showing that big functions/classes/ modules should be broken down into multiple parts, but at the same time, too much division also hurts.

Contents:

Complexity and working memory

Complexity is fundamental in software engineering. The vast majority of time needed to develop software is spent on fighting complexity.

Brooks makes the distinction between essential and accidental difficulties in software engineering, and argues that complexity is an essential difficulty:

The complexity of software is an essential property, not an accidental one. Hence, descriptions of a software entity that abstract away its complexity often abstracts away its essence. Frederick P. Brooks Jr

A good introduction to the distinction between essential and accidental can be found in the short video by Kevlin Henney.

As the complexity of our systems constantly increases over time, we have to improve our techniques of fighting complexity. Related to this, I find the following paragraph from Brooks very important, but often overlooked:

In most cases, the elements interact with each other in some nonlinear fashion, and the complexity of the whole increases much more than linearly. Frederick P. Brooks Jr

I would be bold enough to assert that if one masters complexity then one masters software engineering.

The main obstacle of managing complexity is our mind. We simply don’t have the power to grasp complex things all at once. We do it in small chunks. The theory says that the capacity of our working memory is very limited. Early models claimed 7 different things (plus or minus 2); recent studies claim that without any grouping tricks, the memory is generally limited to 4 different things.

Let’s do an exercise: close your eyes and then try to say out loud, without looking, the content of the previous paragraph. There is a high chance that you won’t be exact. Remembering natural language it’s relatively easy as it contains a lot of redundant information and a lot of structure; moreover, it has a semantic meaning, which is far simpler to remember compared to randomness.

For developing software we need to utilize the working memory to be able to work with multiple parts at once. But if people find it hard to keep in the working memory a simple paragraph, how can we expect to remember the complexities of a software system. They simply can’t.

Don’t despair: the fight is not lost. Software can be organized similarly to natural language to improve its capacity to be kept in working memory (or simpler, readability). Here are some techniques that help in increasing the working memory:

- chunking (grouping)

- confronting mental model with reality

- mnemonics

- repetition

- etc.

Think about a novel. Even if we don’t have the capacity to store all of it into our working memory, we can still manage to remember it afterward; we can remember certain details of the novel, we can correlate between different parts and we can make inferences based on that. We should aim for the same thing with software. (At this point I’m tempted to write an entire blog post to analyze the parallels between structuring a novel and structuring software.)

I argue here that the structure of a software system contributes the most to its readability. We need to organize software in such a way that it both covers the essential complexity and it is easy for us to fit it into the working memory.

Food for thought

As I'm writing these paragraphs, I'm wondering why software engineering has such negative views on repetition; we are thought everywhere to reduce repetition. But, can a form of repetition be used to actually improve the readability of the code?

Grouping complexity

A starting example

Let us take an example of complexity and show how we can use grouping to make it easier to understand.

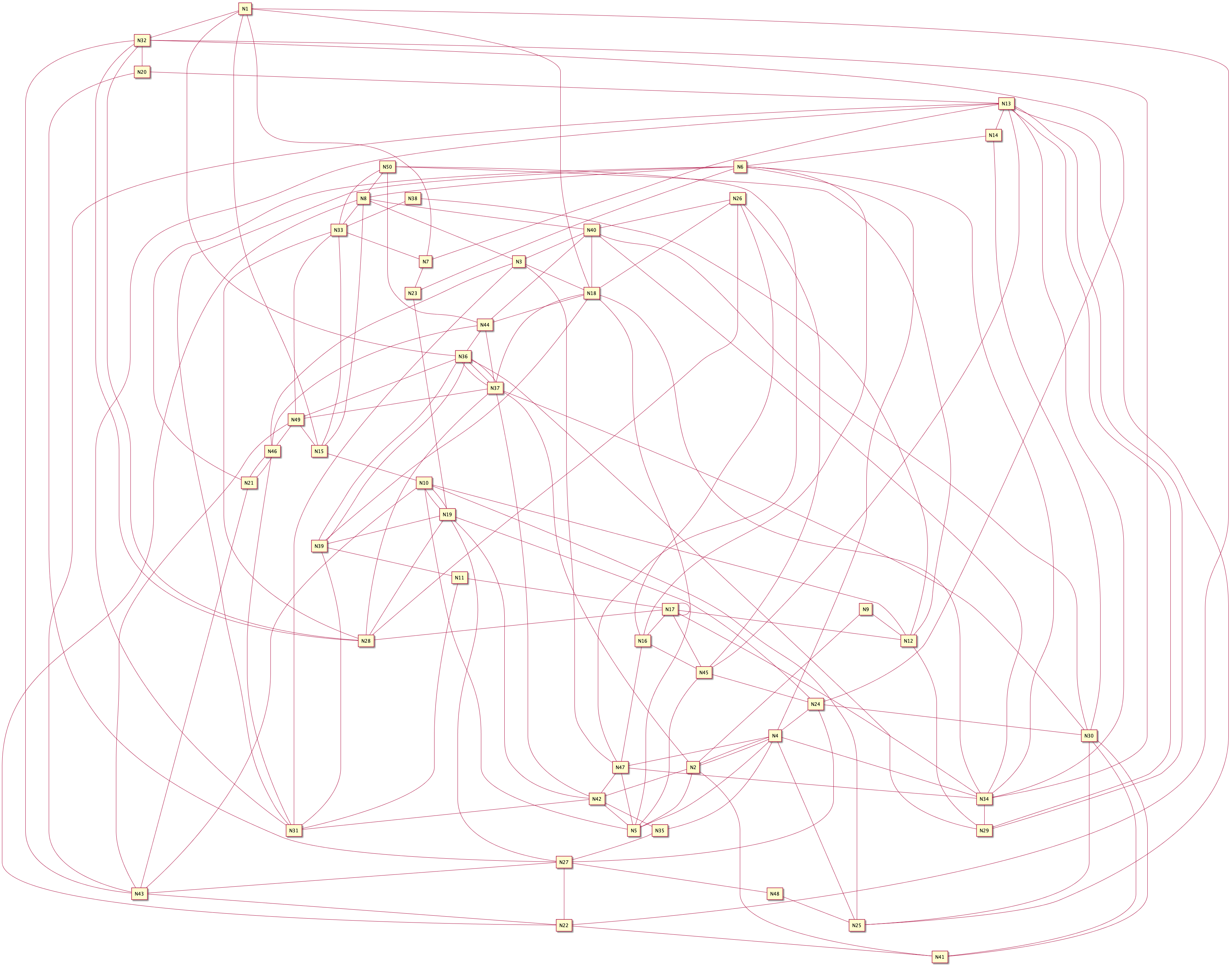

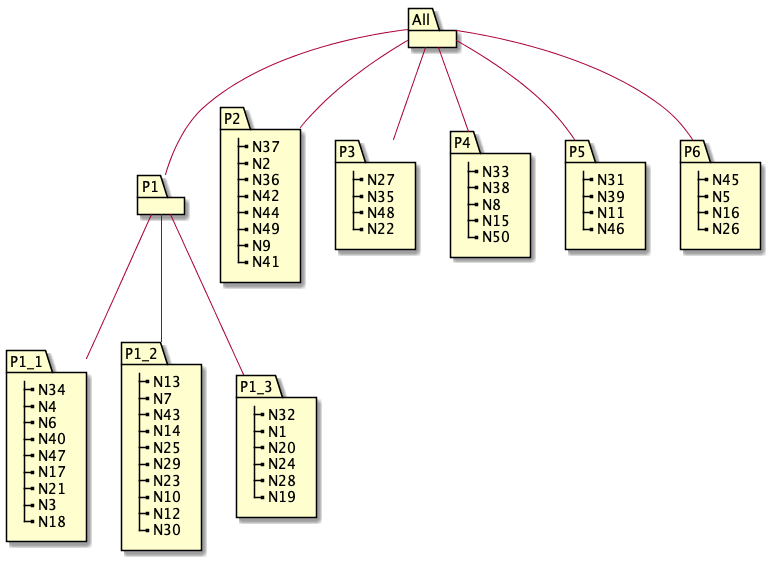

The following picture attempts at depicting complexity:

We used 50 nodes, and we randomly generated 150 links between these nodes. That means 6 links per node, on average. This is not even that bad, compare to software structure.

You can think that each node represents a concept in our software; they can represent instructions, blocks of code, functions, classes, packages, etc. We can apply the same idea to all the levels of abstractions found in our programs. But, for the purpose of this post, we abstract out their source, trying to represent an abstract complexity.

I strongly believe that most of the readers would find this diagram too complex. A program that looks like that and has no other structure is a big mess.

To solve that problem, most programs add structure (think about structured programming). That is, try to group the items; by doing that, we change the way individual elements interact into two problems: how elements within a group interact, and how do the different groups interact.

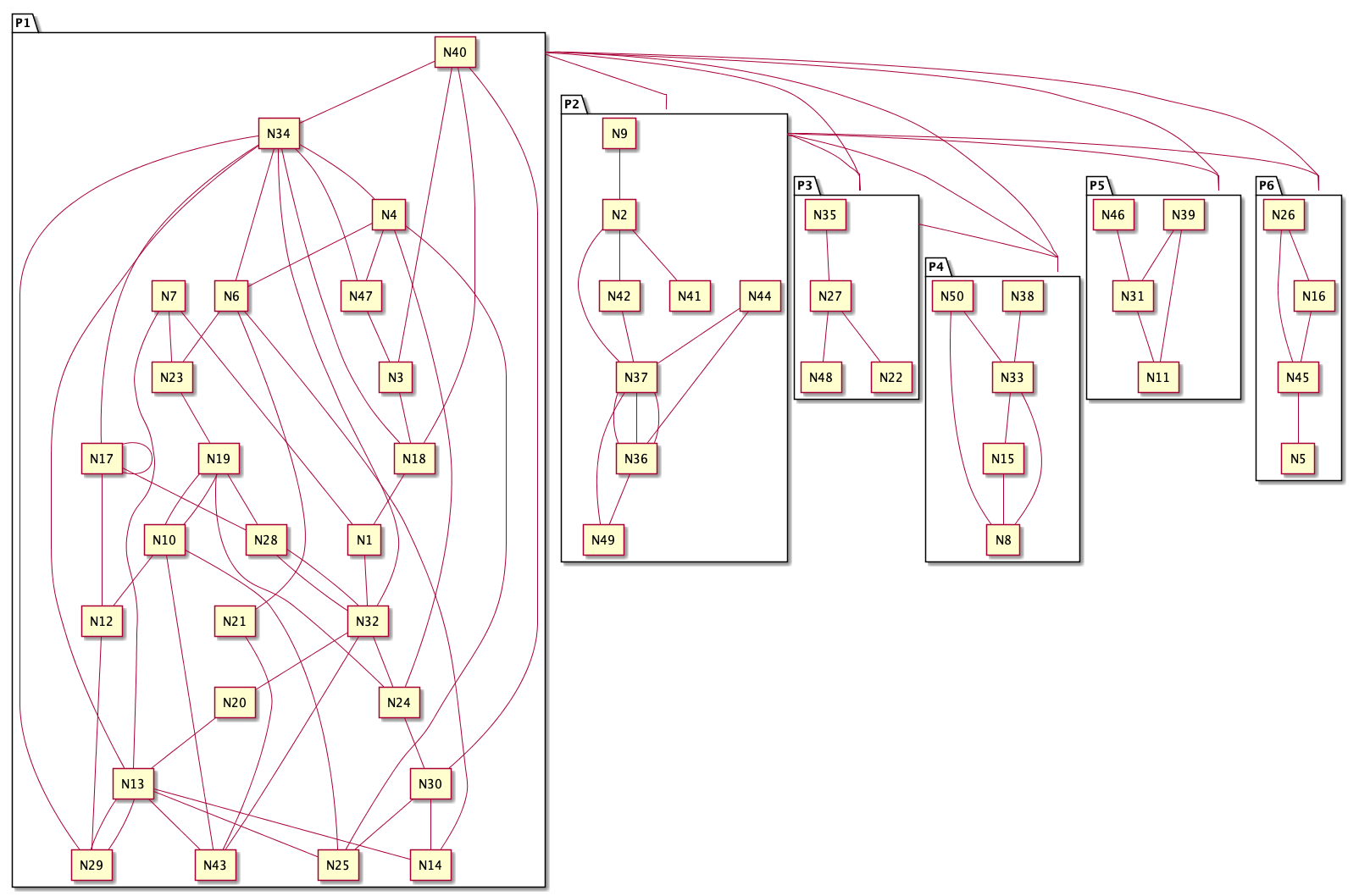

An example of grouping our elements from Figure 1 into 6 groups is presented in the following picture:

Although we have the same nodes, and the same relations, suddenly the picture becomes simpler. The interactions inside a group are easier to visualize, and multiple interactions across groups are replaced by just a few interactions at the groups’ levels.

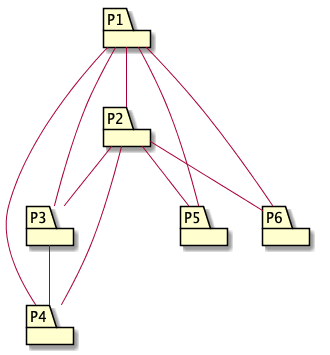

The interactions between groups are also simpler, as shown by the following picture:

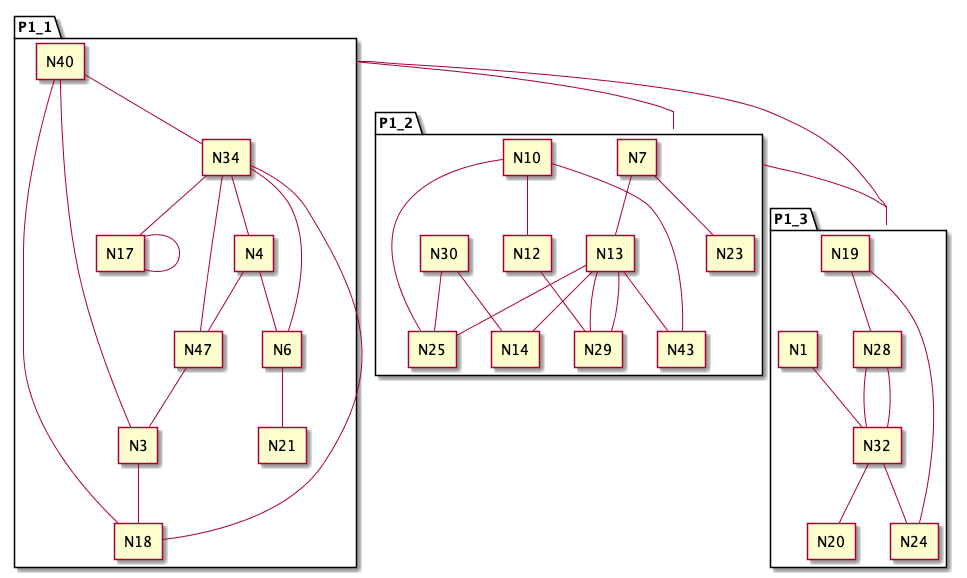

And the nice thing about this grouping process is that we can apply it recursively. For example, the elements inside P1 from Figure 2 are still too complex. We can arrange them into 3 groups in the following way:

I believe most of the readers would agree that reading the diagrams after grouping is easier than reading Figure 1.

The following picture shows the overall structure we reached after our transformations:

Interlude: grouping vs decomposition

At this point, we need to stop and ponder at the approach we are taking. We don’t approach this from a typical “decomposition” point of view. There, we would associate meaning to our elements and would try to find a decomposition or a structure to the system to have more meaning. We would try to maximize changeability, independent development, comprehensibility, etc. (see On the Criteria To Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules by D.L. Parnas). But, in our approach, we are deliberately ignoring the meaning of all these elements, and just concern about the fact that there are links between them. We try to look at the program from a more quantitative approach: what would be the granularity level of the division? Do we need a fine-grained or a coarse-grained division?

We are using here grouping, which implies a bottom-up approach. But the same things apply if we would take a top-down approach. We are more concerned about analyzing the complexity of the end result than what method we take to reach that point. Long story short, the reader can easily apply the results from here to the problem of decomposition.

Pros and cons of grouping

After the previous example of how complexity can be tamed, the reader may be tempted to assume that grouping is always a good thing: it allows us to simplify the structure of pure complexity. But it’s not always like that. Let’s investigate.

| Consequence | Pro/con |

|---|---|

| reduces the complexity inside groups | pro |

| allows a reader to better focus on a part of the structure | pro |

| adds more elements, increasing complexity (e.g., the new grouping nodes) | con |

| a reader needs to switch abstraction levels while moving up/down across the grouping tree (i.e., from N18 to P1_1 and P1 and the other way around) | con |

| decreases the total number of links | pro |

| moves links at a higher level -> requires the reader to change focus | con |

| some direct links may be transformed into multiple links as we navigate different groups (i.e., moving from N18 to N5 requires now 5 links instead of one: N18->P1_1->P1->All->P6->N5) | con |

Please note that to keep things easier, our grouping does not mean rewriting the basic elements. It just adds wrappers on top, possibly rewriting the connections between the items. For example, if our initial nodes were functions, by grouping we mean adding new functions that call the original functions but in a different manner. Continuing this example, Figures 2-5 added functions P1, P1_1, P1_2, P1_3, P2, P3, P4, P5 and P6 that would call other functions in a slightly different way.

The conclusion that can be taken after reading the above table is that we need to apply grouping with moderation. Let’s not investigate some major alternatives.

1-element grouping

This is probably the worst kind of grouping. You have one element, and you add another one, without reducing any complexity; keep the same number of links, and decrease focus. A bad deal.

A class that just wraps another class without adding any extra functionality is a typical example of this case.

In general, please avoid 1-element grouping.

2-element grouping

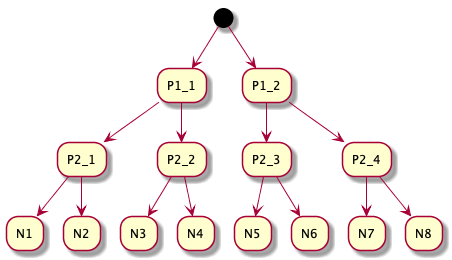

This would correspond to creating a binary tree of groups, like in the following picture:

Consequences:

- the number of elements will essentially double (i.e., for 8 initial elements one would have 7 additional group elements)

- we add 2N - 1 new links for grouping

- refocus is a problem, as to move from one element to another we typically have to traverse a large part of the tree (in the above tree, a connection between N4 and N5 would require 6 link traversals)

- grouping is so small (2 elements + parent group) that it doesn’t even fill the entire working memory of the brain

This is something that we often meet in software development. Some developers tend to add new classes/functions for every small thing that needs to be added on top of an existing functionality. These new classes/functions do not have a new responsibility, they just group other lower-level program entities.

This 2-element grouping tends to look like something called Classitis by John Ousterhout in his book A Philosophy of Software Design. Classitis appears when we religiously apply the “classes should be small” mantra.

In general, this grouping tends to be less ideal.

Grouping of a large number of elements

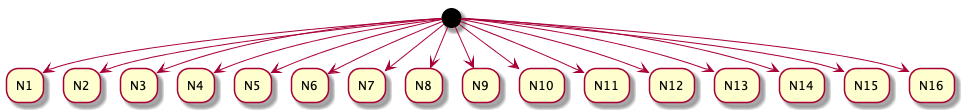

At the opposite extreme of 1-element and 2-element grouping is the grouping in which there are a lot of elements in one group. Something like this:

Now, we haven’t shown in this tree diagram the relations between the elements, but one can imagine that there are complex relations. It’s almost like having no grouping at all.

Consequences:

- doesn’t reduce complexity; it’s just like having no grouping

- doesn’t increase user focus for the nodes inside the group (it’s just like looking at the original complexity)

- the number of links does not decrease by a large margin

This is also something to be avoided.

The golden mean

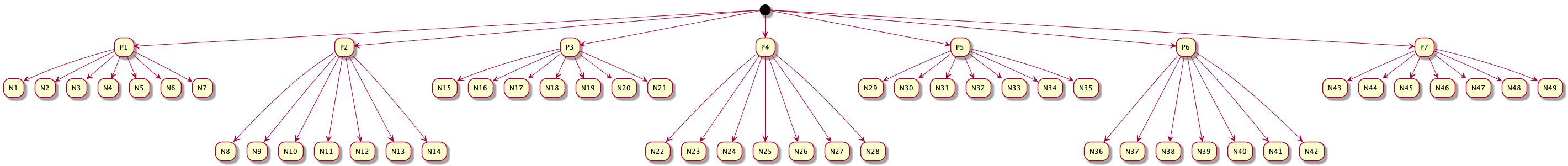

A compromise between the two extremes would alleviate the downsides of these and would provide the most benefit. Here is an example of a tree for a 7-element grouping:

Consequences:

- reduces, and provides an upper bound to the complexity for the nodes within a group

- allows the reader to better focus on the complexity inside the group (we actually choose the number 7, because of the studies in psychology that people can keep 7 items in working memory)

- the number of new elements is not that big (here, we added 8 new group nodes for 49 elements; previously, we added 7 new nodes for a 2-element grouping of 8 elements—about 6 times better)

- the movement up/down across the tree is reduced, as the tree height is kept relatively small

All these seem to indicate that such a grouping would be better than the two extremes (1/2-element grouping and a very large number of elements per group). Although we add new nodes and links, we manage to keep their number small, while making sure that we reduce complexity.

As we started our discussion on complexity by using Aristotle’s division between essential and accidental, it seems natural to invoke Aristotle once more when discussing the golden mean. Indeed, Aristotle places the golden mean principle as a foundation stone of his Ethics (see details).

Virtue is the golden mean between two vices, the one of excess and the other of deficiency. Aristotle

If we want to be virtuous in software engineering, we need to be able to balance between opposing factors. In our case, we need to balance between having groups with a small number of elements, and groups with too many elements.

Main takeaways

Similar to Aristotle’s theory, this post is not intended to give the reader a decision procedure on splitting complexity. We aim at providing a theoretical framework to enable practical reasoning. This reasoning should be always grounded by the realities of each independent project, and they cannot be determined upfront.

One should always assess the cost in understanding for adding new grouping (new abstraction) to one software, and decide what type of abstraction is the right one to use.

It would be safe to summarize the takeaways as following:

- don’t try to divide the complexity into too many small pieces; you are just creating a complexity at an upper level

- not dividing complexity is also bad; the reader will not be able to follow and understand the complexity

- try to hit a golden mean between the two extremes

- one default answer for the question “what would be a good division?” would be: just enough so that a small part can fit in the reader’s working memory rather easily

Next steps

Ok, ok, theoretical framework and all that, but how can we apply this in practice?

Well, it turns out that, if the reader avoids the cookbook type of books/articles, there are a lot of good materials over there that take a balanced approach. Here are just a few of my favorites:

- Frederick P. Brooks Jr, The Mythical Man-Month book. A classic in software engineering, not only introduces this analysis of essential vs accidental complexity, but it provides good insights of various software engineering processes and provides balanced views in the matters.

- John Ousterhout, A Philosophy of Software Design book. It provides a nice analysis of the software problem and a structured approach to creating good designs. What I really like about the book is its argumentative style; all the conclusions are well explained, almost like being proved.

- Kevlin Henney’s talks. For example, watch: What Do You Mean?, Engineering Software, Clean Coders Hate What Happens to Your Code When You Use These Enterprise Programming Tricks, and Agility ≠ Speed. What I really like about Kevlin’s talks is the balance that he applies to the subjects that he talks about; he always knows not to take one idea too far; probably the best example of balancing that I’ve met in software engineering teaching.

One can take the findings from this post and apply it to a lot of problems in software engineering. Take for example the FizzBuzzEnterpriseEdition example that Kevlin is discussing. One can easily remark the fact that the grouping granularity of the implementation is completely wrong. First, it tends to create new groups for every small feature in the problem domain; that’s why it has 89 Java classes. Secondly, one can argue that there is not enough grouping at some levels. Take for example the grouping in impl/factories: we have 15 elements in that folder that do not communicate inside the group but only outside of the group. Just adding files in the same folders do have the same effect as the grouping we are discussing here, as it does not reduce complexity. Therefore, we have a lot of nodes at the high-level that are not properly grouped. The implementation suffers from both extremes of grouping.

That’s just a small taste on how we can apply this reasoning for practical problems.

Keep truthing!

Comments