Exceptional exploration (2)

To use or not to use exceptions? That is the question. Asked again.

In the previous post we explored the performance implications of various error handling mechanisms. Here we continue our exploration of error handling mechanisms but focusing on modifiability – i.e., the ability of the code to be easy to write and be modified in the future.

We argue that exceptions are both a good thing and a bad thing. We attempt to divide the scenarios into multiple categories, and we provide reasons pro and con for each category. The goal is to find the contexts in which it’s better to use exceptions. The answer may be surprising: there are more cases in which manual error handling is better than using exceptions. If only standard library would support non-exception policies…

Intrusiveness

Exceptions – minimal example

Let us take a simple example as a basis for our discussion. Let’s assume that we have three functions f1, f2 and f3 for which we need error handling, and we want to call them one after another. The main assumption is that, if one function fails, the others shall not be called.

Using exceptions, the code would look like the following:

try {

f1();

f2();

f3();

} catch (const std::exception& ex) {

// ...

}If we want to propagate the error up one level, we would do something like:

void callAll() {

f1();

f2();

f3();

}

try {

callAll();

} catch (const std::exception& ex) {

// ...

}The main advantage of exceptions is that they are the least intrusive. We are not required to change the the way we write f1, f2, f3, or callAll in order to handle the exceptional cases (well, sort of).

Error codes – minimal example

There are multiple ways in which the functions that detect the presence of error cases can report the errors to the caller. In our example we will make the functions return a bool indicating the success of the function (false means presence of an error). Yes, we are losing the type of the error, but this is not our focus right now.

Using return values, the similar code would be:

bool ok = f1();

ok = ok && f2();

ok = ok && f3();

if (!ok) {

// ...

}and:

bool callAll() {

bool ok = f1();

ok = ok && f2();

ok = ok && f3();

return ok;

}

if (!callAll()) {

// ...

}Compared to the exceptions version, this is slightly more invasive, but not that bad. We would make all the functions that can somehow fail return a bool value.

The main distinction from the exception case is that we are handling the errors manually at the callee side. As we shall see later, this can be both an advantage or a disadvantage.

Other error handling alternatives

The bool return code cannot keep too much information. We can however easily imagine return code classes that will generalize the return value with an error. A simple generalization is to make the return code some kind of integer value. Another possibility is to store dynamic data for the error. Or maybe a complex structure with a predefined format, with the possibility to extend it with more error information. In the previous post, the Expected<T> variants are examples of this strategy of generalizing the bool return code.

Regardless of the method in which we pack the information, our return value must support the following:

- be able to indicate whether we have a failure and success

- carry enough information to be able to properly act on failures

- provide a quick way to chain multiple calls (i.e., the

ok = ok && ...idiom) — no, we are not discussing about monads in this post

These alternatives are not hard to implement, and don’t add value to our discussion, so, for simplicity, we will keep referring to returning bool as the representative way of handling errors by hand.

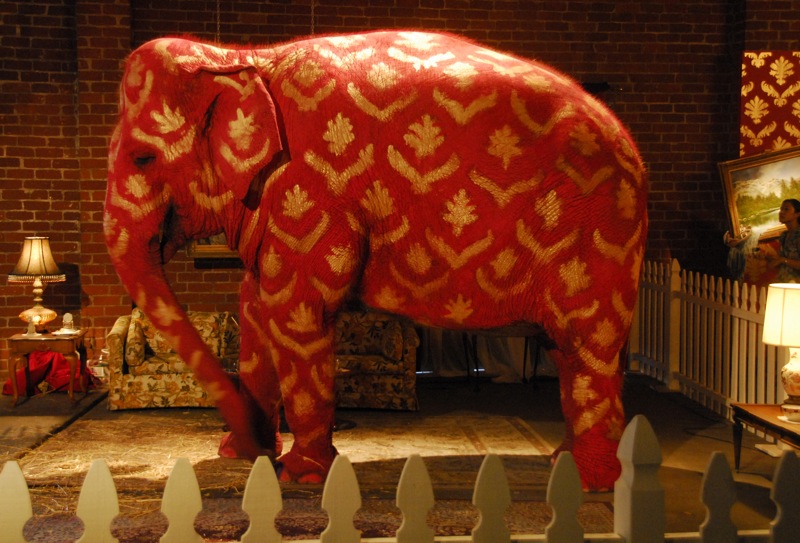

The elephant in the room

Let’s now turn our attention to the typical types of failures. A simple list of these failures would be:

- logical errors

- input data error

- memory allocations

- file I/O

- networking

- etc.

Except one, all the items in the list are somehow infrequent, or isolated in most of the software applications. That is, there is a low probability that 99% of your code is concerned with file I/O; and if you are doing that much I/O, then probably you would need to take the error handling mechanism to the next level.

The elephant in the room is memory allocation. It is hard for me to imagine applications in which memory-management is not pervasive. Not only that you would have heap allocations, but you would probably have heap allocation all over the place.

Let us think of typical data in classes. In general, it can contain one of the following:

- numbers and bools

- other structures (by value)

- pointers to other data structures

- strings

- common data structures (vectors, maps, etc.)

Except the first two parts, everything needs memory allocation in one way or another.

Generalizing a bit, we can say that typical classes need memory allocation, directly or indirectly. As in C++ we use classes for nearly everything, we can immediately jump to the conclusion that typical C++ applications use memory allocation pervasively.

Therefore, the problem that we immediately have is that almost all parts of our software can fail due to memory allocation.

Impact of memory allocation

Let’s consider a simple class:

struct Borrower {

int id_;

std::string name_;

std::vector<std::shared_ptr<Book>> borrowedBooks_;

Borrower(int id, const char* name);

// ...

};Because of memory allocation, this class can fail at the following operations:

- initialization constructor

- copy constructor

- assignment operator

- etc.

If we are using exceptions, there are no changes that we need to make in order to handle errors. But the consequence is that the vast majority of the code can throw exceptions.

If we are using manual error reporting (i.e., exceptions are banned), we start to have a series of problems:

- constructors cannot return error indicators, so we cannot allocate memory into them

- we need to have a separate

initfunction corresponding to our initializing constructor – two step initialization - copy constructor needs to be disabled

- assignment operator needs to be disabled

- a

assignmethod is needed to implement copy constructor and assignment operator - same for move constructor and move operator

- we cannot use the C++ standard library anymore – it throws exceptions

using std2 = MyNonThrowingStdLibImplementation;

struct Borrower {

int id_;

std2::string name_;

std2::vector<std2::shared_ptr<Book>> borrowedBooks_;

Borrower(); // puts the object in an invalid state

bool init(int id, const char* name);

bool assign(const Borrower& other);

// ...

};The changes to the class itself doesn’t seem too big by themselves, but the problem appears on the caller’s side. We have far more functions that need to be called. For example, we need this code:

int id = 0; // cannot properly initialize this here

bool ok = getId(id);

std2::string name; // again, no proper initialization

ok = ok && getName(name);

std2::shared_ptr<Borrower> borrower;

if (ok)

borrower = std2::make_shared<Borrower>();

ok = ok && !borrower.empty();

ok = ok && borrower.init(id, name.c_str());instead of:

auto borrower = std::make_shared<Borrower>(getId(), getName());We have 9 lines of code instead of just one; this is a huge impact introduced by the no-exceptions policy.

Key point

Treating memory allocation failures by hand leads to excessively complex code.

Whenever considering modifiability costs, you need to consider how much easier is to introduce mistakes in the above code; there are so many things to ensure manually. And the existing tools are not necessarily very helpful on the possible types of mistakes the users can make.

Besides the fact that it’s harder to write and to maintain, it also has understandability problems. It’s much harder to understand what the code really does, because the plumbing takes much more space than the actual important logic.

On top of these, you need to add the cost of developing a new standard library, because most of STL will throw.

The hidden costs of exceptions

Life with exceptions is not all that rosy. The code may be smaller, but there are a lot of hidden assumptions and concerns. Let us illustrate that by starting with the above example:

auto borrower = std::make_shared<Borrower>(getId(), getName());What are all the places that can throw exceptions in the above code? Let’s count them:

- getId may throw

- getName may throw

- Borrower constructor may throw

- make_shared may throw

If we would have an assignment operator for some other class, we may suspect that to be throwing as well.

So, even for a small amount of code, the programmer shall reason about all these possible throwing points. Throwing in an unexpected point may have unwanted consequences. To better illustrate this point, let’s look at the following example:

void Borrower::reset(int id, const char* name) {

this.id_ = id;

this.name_ = name;

}Have you spot the problem here? The second assignment may throw, leaving the id changed but not the name. That can violate some of the preconditions of the class. In practice, it is really hard to spot these kinds of bugs. I would argue that it’s harder to spot correctness issues with this code than in the case of manual error handling.

To fix this, we need to provide strong exception guarantee (see Wikipedia page or cppreference for more information of exception guarantees). The code would look like:

void Borrower::reset(int id, const char* name) {

auto nameCopy = name; // can throw

this.id_ = id; // nothrow

this.name_.swap(nameCopy); // nothrow

}The code is not much more complicated, but just uglier to write.

Please also note that we don’t have the proper tools to find (and fix) these kinds of error. The programmer may need to type far more to specify all the invariants of the class, so that a tool can attempt to detect bad exception handling code.

I agree that the chance of assignment throwing is extremely low, but anyway, this is a correctness issue. If we can close our eyes to this issue, we may be better of by saying that simple memory allocations will never throw.

Key point

Using exceptions allow the introduction of subtle correctness bugs if the programmer is not extremely careful.

Where and how to handle isolated error cases

As opposed to pervasive error handling, by isolated error cases we mean scenarios in the code in which the operation that may fail is explicit. One good example of this kind is file I/O. In order to have some I/O error case, you have to manually perform some I/O operation.

We want to broadly cover our analysis from the following perspectives:

- where would the error be handled relatively to the source of the error

- whether we shall do explicit error checking or we shall use implicit error checking with exceptions

Things are slightly fuzzier in this section, but regardless, we strive to provide enough arguments to make a solid case.

Where to handle the errors?

For the first point, we have the following options:

- as close as possible to the top-level of the application

- as close as possible to the source of the error, at the point that we have all the context for the operation that failed

We argue that the first point is bad. Most probably you don’t have enough information to react to the error, so you will just end up logging and ignoring the error (showing it to the user is typically a bad thing – imagine your favorite word processor suddenly popping a “Cannot write tmpXYZ.dat file!” error box).

If, on the other hand, we would react at the place that we have the best context of what failed, then we can properly react to the error. Sometimes it’s ok to just ignore the error, and sometimes we can take alternative actions. For example, on a network error, we may retry in a few seconds, or we can try contacting another server.

Please note that this may involve passing the error across several different layers. But, most of the time the error shall be translated to indicate an error in the API that the caller of the layer knows about. For example, a socket error may translate into “cannot download a file”, which can translate into “cannot continue transaction”, which can translate into “user operation failed”. We are still handling the error at the closest level, but this actually means “fail the parent operation”.

Explicit error handling or exceptions?

The question is to chose between this:

void processFile(const char* filename) {

try {

// Open the file for reading

MyFile f{filename, "r"};

// Read the content

std::string content = f.readAll();

// Do something with the content

doProcess(content);

} catch(const CannotOpenFile& ex) {

onCannotOpenFile();

throw CantProcessFile();

} catch(const CannotReadFile& ex) {

onCannotReadFile();

throw CantProcessFile();

}

}and this:

bool processFile(const char* filename) {

// Open the file for reading

MyFile f;

if (!f.open(filename, "r")) {

onCannotOpenFile();

return false;

}

// Read the content

std::string content;

if ( !f.readAll(content) ) {

onCannotReadFile();

return false;

}

// Do something with the content

doProcess(content);

}They are very similar. The no-exception variant has the slight advantage that the error handling code is quite near the code that can fail. Moreover, it’s more explicit, so it should be harder to miss error checking. By looking at the above code you can see that all error cases are treated properly. But you cannot do the same if you are looking at the exceptions variant; you are not sure if the code can only throw two types of exceptions and whether the read operation throws CannotReadFile exception and not ReadError.

If the code can really fail, then I would argue that it is important to be able to properly check the error cases. If you are explicitly calling functions that may fail, then you should also explicitly handle all the errors generated by them.

Because error handling code should be close to the error generating code (see above), using exceptions should not actually save us anything.

When dealing with errors, explicit is better.

Key point

For handling isolated errors, prefer being explicit; exceptions don't help much.

If the room is too small, consider moving the elephant

If for the isolated error handling it may be better to use explicit error handling, then why can’t we reach the same conclusion for handling memory allocations? Maybe the problem is not with the error handling mechanisms but with memory allocation.

Let us divide the memory allocation problem in two:

- allocating small and medium-sized objects (i.e., strings and vectors); let’s say less than 1MB

- allocating large chunks of memory

When we say that memory allocation is pervasive, we are actually referring to allocating small and medium-sized objects. Allocating large chunks of memory is, for most applications, relatively infrequent.

The reader should guess by now where we are heading with this:

- assume that small and medium-sized allocations cannot fail

- perform explicit error checking in the case of allocating large chunks

Explicit error checking for large chunk allocation doesn’t pose any particular problems, so let’s focus on the assumption that small and medium-sized allocation cannot fail.

For most systems, if allocating 1MB fails, the system is performing extremely bad for a far longer period of time. Things would start to fail long before this point. The application shall never reach this state. A good example is from an embedded project that I worked from: we had a strict memory budget, but it was not enforced by the OS; we could consume twice the amount of memory that we were allowed, and OS will not fail our memory allocations; the irony was that other processes on the OS would crash much faster than our process.

You can find such examples anywhere. Think about how would games perform if they would try to go until the OS will not be able to give them any memory. Think about the performance of desktop applications who will use large amounts of swapped memory. Think about mobile apps and the effects on your battery life.

An application that waits for the OS to indicate that it ran out of memory is a poorly design application.

There are projects (i.e., especially in embedded software) in which maintaining some small memory footprint is essential. But in those projects, custom allocators are the norm.

Custom allocators. Maybe the solution lies here.

Recovery from allocation failures

There are several things that an application can do when an allocation failure occurs:

- give up; crash

- restart itself

- attempt to free some memory

The first two options are obvious. The third one is more debatable. People often think that the the information related to who owns the memory is found along the callstack of the memory allocation failure. Except bugs, most of the time this is not true. Think for example of multithreaded applications or applications with event loops.

The typical scenario is something like:

- something allocates more memory in one part of the application

- somebody else tries to resize a vector (or something) in another part of the application and runs out of memory

What would be then the right place in which to manage these allocation failures, and what would be the right steps? I haven’t performed a good analysis on this, but I believe the answer should be along the following lines:

- application uses its own custom allocators

- application defines a memory alert limit and installs a handler whenever the memory reaches that limit

- the memory alert limit shall be chosen so that the application still operates when the limit is reached

- when the application allocates more memory than this limit, the handler will be called (during the memory allocation); this handler can do one of the following:

- remove some memory

- schedule a cache cleanup in the application to happen soon enough

- whenever the application goes beyond the alert limit, it will be soon corrected, so that it will reduce its memory impact

- unless there are bugs in the application, it will roughly stay below the memory alert limit

This approach is of course dependent on the type of the application. Nevertheless it shall be applicable to a wide variety of applications.

Key point

It is better to handle memory allocation failures with a custom allocator and a memory alert limit than with tons of logic sprinkled all around the code.

Mandated correctness

There are however cases in which correctness is mandated and it’s the top priority of the code. That is, we must be sure that:

- all allocations are checked

- all subscripting is checked

- all operations that can fail are checked

- error reporting doesn’t have any bugs

In this case, the custom memory alarm limit trick is not working. We cannot guarantee that in fact the application does not have allocation failures (we just reduce the probability to something extremely small).

For this, it’s tempting to use exceptions. But again, we’ve shown than it’s much harder to guarantee exception code doesn’t have bugs than guaranteeing that manual error handling code doesn’t have bugs.

Here is a big trade-off. Using exceptions will make you reach into more areas and implement error-handling non-intrusively, but then, error handling code not being explicit, it’s hard to detect bugs. If correctness is far more important, then explicit error handling shall be the norm.

Depending on the correctness requirements, when compared with usability requirements it may turn out that exceptions are easier to deal with than explicit error handling.

Key point

In general, if correctness is top priorities, explicit error handling should be preferred. But there may be scenarios in which exceptions can be preferred.

Mandated predictability

If the project has hard real-time constraints, then all code must have a predictable execution cost. We shall be able to reason about the worst execution time.

As exceptions are known not to have a predictable execution cost, they shall not be used in these scenarios.

Also, it’s worth noticing that memory allocation and deallocation have low predictability, and therefore a lot of effort needs to be placed into custom allocators that will present better predictability.

Conclusions

Let us provide a summary for when it’s appropriate to use exceptions and when it’s appropriate to use explicit error handling.

Using exceptions is appropriate when:

- you want to reuse other libraries (i.e., standard library) that mandates the use of exceptions

- in cases in which you are not willing to write your own memory alarm

- in some cases in which correctness is important, but not extremely important

Using explicit error handling is appropriate when:

- you can solve the memory allocation failures at the allocation level

- handling accidental failures (i.e., failures that are not pervasive through the code)

- correctness is very important

- predictability is important

- the code can actually fail (see previous post on performance)

Please also remember from the previous post that in terms of performance, using exceptions is not necessarily preferred.

Key point

If it wasn't for the fact that a lot of libraries mandate the use of exceptions (including standard library), I would recommend not to use exceptions in C++ projects.

Key point

It is a pity that a language that brags with you don't pay what you don't use, that is designed for embedded and real-time systems, doesn't have good support for not using exceptions.

Hope this will be addressed in the future versions of C++. If it’s not way too late.

Keep truthing!

Comments