Tasks, threads, and execution

My previous posts on tasks and concurrency (Threads are not the answer, Look ma, no locks and Modern dining philosophers) ) all talk about tasks. But after all these posts, I’ve got the same question back what is the difference between a task and a thread?, in various forms.

This blog post is aiming at making some light on this difference.

Contents:

Definitions

Task definition

A task is an independent work unit that needs to be executed at some point.

Thread definition

A thread is an OS execution context that allows executing a stream of instructions, in sequence, independent of any other instructions that can be executed on the CPU.

If a task is a user-level programming abstraction, a thread is an OS abstraction.

A task is better described as a lambda with no parameters that return void:

[]() {

// some code

}or, more generally by any programming construct that binds to a function with no arguments that return void:

using Task = std::function<void()>;The above code is written in C++, but similar abstractions can be found in most of the popular languages.

A thread is the OS abstraction needed for the CPU to execute one or multiple tasks.

Another way to show the difference is the following code that shows both the thread and the task in one place:

std::thread myThread([]() { myTask(); });Execution

In the previous example, we would run one task on one thread, and both the thread and the tasks are known in advance. That is just an execution policy; we can invent other execution policies. For example:

- run multiple known tasks of different types on a statically known thread;

- run the same task type multiple times on a statically known thread;

- run a known task on a thread determined dynamically;

- run a series of known tasks on a thread determined dynamically;

- run tasks determined dynamically on threads determined dynamically, etc.

For the purpose of this post, we call execution policy, or simpler execution, the rules that govern the mapping between tasks and threads.

For simplification, we assume there are two main policies:

- a static one, in which we know all the details of the threads and the tasks and of the assignment from tasks to threads;

- a dynamic one, in which the tasks do not know how many threads there are, and on which threads they would be executed, and similarly, the threads do not know which tasks are to be executed.

I would argue that, in the vast majority of cases, the second policy is better. It provides the best flexibility, it’s composable, and easy to work with. Moreover, for average use-cases, it can have better performance.

In the static concurrency scenario, tasks are statically bound to threads. The threads will know exactly what tasks are going to be executed. If one uses this policy, then the distinction between threads and tasks becomes less important.

Here are some notable examples of this execution policy:

- we know upfront how many threads we want, and we know what work each thread needs to execute;

- the thread has a loop and executes the same thing over and over; typically one can think of the loop body as being the task assigned to the thread;

- the thread has some kind of task queue from which it executes tasks (semi-static concurrency).

In the case of dynamic scheduling, if we ignore a lot of implementation best practices, we can think of the execution policy the following way:

- we have a pool of worker threads (dynamically adjusted);

- we have a global pool of tasks that need to be executed;

- the worker threads extract and execute work from the pool of tasks.

In practice, such an execution policy is implemented with work-stealing. Each worker thread has its own queue of tasks, and whenever it consumes all the tasks it will attempt to steal tasks from other worker threads.

In the following sections, we present some of these examples, with their pros and cons.

One thread per task

This scenario is somehow a mix between static execution and dynamic execution. If we think of the creation of each task, then we know exactly which thread is associated with it, and therefore we are in the static case. If we think about the fact that we don’t necessarily need to know all the tasks that we are executing, then this sounds more like a dynamic execution policy.

This approach is typically avoided as it has performance problems:

- creating and destroying threads is typically expensive;

- too many threads at a given time are not optimal.

Synchronization between tasks is typically performed with thread-joins, which are essentially blocking mechanisms. Depending on the type of problem solved, this can generate additional performance problems.

Static assignment with thread loops

In this case, the number of threads is typically known in advance and the work is typically statically assigned.

Let’s assume that we have 8 such predefined threads in our system. Each thread can execute tasks of a certain kind. If, for example, for the first thread we have 100 tasks, but no tasks for any other threads, then our parallelism is severely limited.

One may argue that this example is intentionally constructed to show this problem and that this doesn’t happen that often in practice. That may be true. But let’s now slightly change the example to make it far more realistic. Let’s assume that the time needed to execute the type of tasks for the first thread is 1 second, while the tasks for the other threads can be completed in 0.5 seconds. Let’s also consider now a distributed load of 100 tasks for each thread. Assuming we have 8 cores, in the first 50 seconds, the first thread will have executed only half of the tasks, while the rest of the threads will execute all their tasks. We still end up in the same scenario as before but with 50 tasks instead of 100 tasks. Instead of using all cores all the time, we are using only one core for 50 seconds.

One can see that this can become a problem for most of the applications, as different tasks typically have different durations.

Another problem with this approach is that it typically entails synchronization with blocking primitives (mutexes, semaphores, etc). Different types of tasks occasionally need to interact. There is no direct way for us to communicate between the threads, so people will tend to use synchronization constructs.

This makes this approach not composable, and of course, there will be performance implications of this approach.

Dynamic execution – raising the abstraction

In a dynamic execution system, we raise the abstraction level. The threads and the assignments of tasks to threads are typically dealt with at the framework level. The end programmer will only have to deal with tasks and interactions between them.

The framework knows how to size the pool of worker threads to achieve the best performance of the platform the code runs. It also knows how to distribute the tasks dynamically to threads to execute them as fast as possible.

Because the tasks are not statically assigned to threads, we can use the dynamic nature of tasks scheduling to implement synchronization. Please see Look ma, no locks and Modern dining philosophers.

The reader probably is familiar by now that I’m strongly advocating for this dynamic execution.

Some measurements

I set up a simple test to measure the performance of a task-based execution policy versus thread-based execution. I test running 8, 16 and 32 tasks in parallel. All the tasks are just simply spinning on the CPU (compute Fibonacci recursively). For each test, I compute the average running time of the tasks. I run these tests with one thread per task, and by using a task-based execution policy (with our GlobalTaskExecutor as shown in Modern dining philosophers post).

The results are the following:

| Number of threads/tasks | One thread per task | Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | 1.1055 | 1.08814 |

| 16 | 2.22686 | 1.09009 |

| 32 | 4.37931 | 1.12871 |

(these were run on a 4-core processor with Hyper-threading, so 8 logical cores).

As one can see, if I create more threads than actual available logical cores, the execution times for the tasks start to increase. That is, if I have 2 threads running a 1-second task on the same core, both tasks would terminate in 2 seconds; the CPU is split between executing bits from both threads.

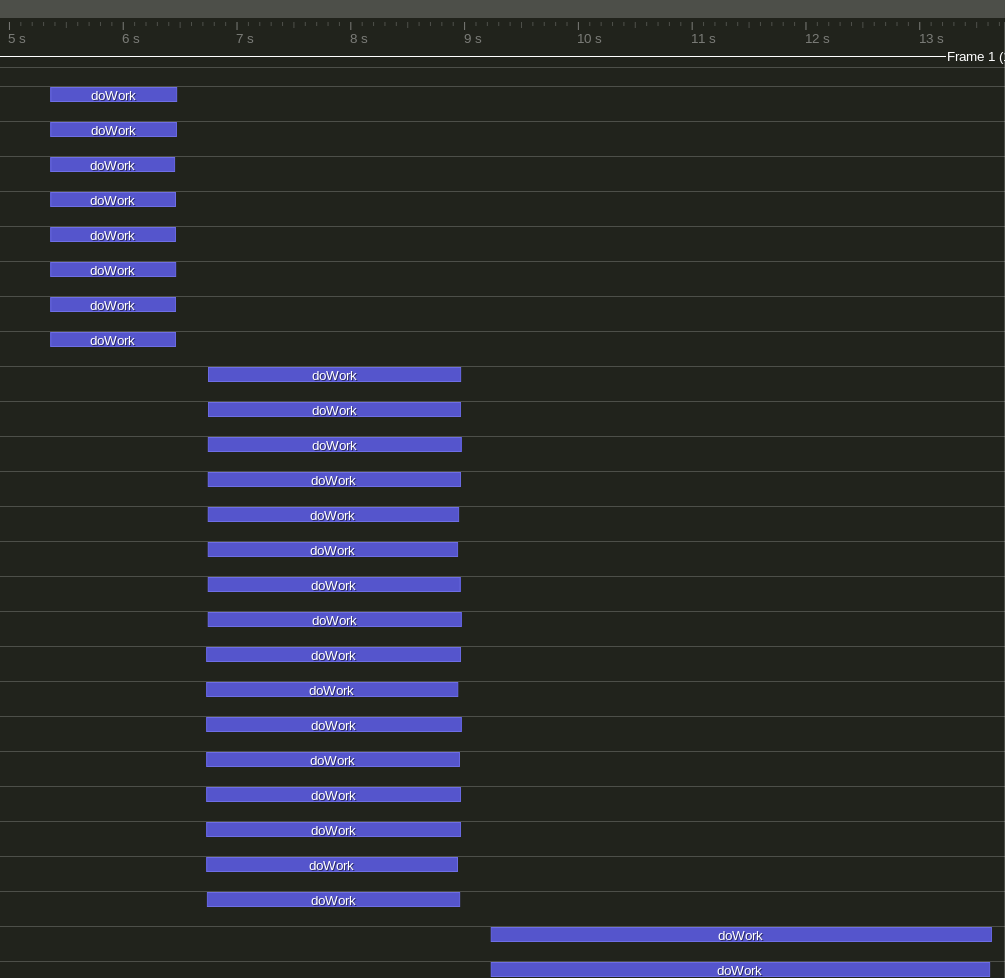

I’ve used Tracy to instrument the code. I’ve added scopes for each task to be executed. In the case of one thread per task, I’ve obtained the following:

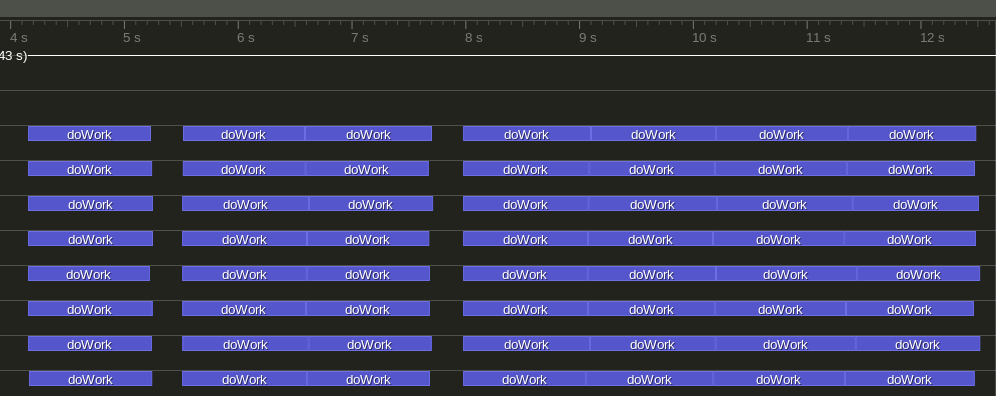

If, on the other hand, I run the tasks with a task-based execution policy like Intel Threading Building Blocks, I obtain the following distribution:

These two pictures shows the main differences between the methods:

- for the time-based execution the duration of the threads is independent of the number of tasks, while for the thread-based execution, the number of threads affects the performance of individual tasks;

- the task-based execution will run multiple tasks in sequence for the same worker thread;

- the task-based execution will reuse threads between tests.

Keeping the same execution speed for a task is really important. For example, in the case with 32 tasks, the thread-based execution will not finish anything in the first 4 seconds. On the other hand, the task-based execution will have finished 16 tasks by then. So, we can say that a task-based execution has better latency than a thread-based execution.

In this particular implementation of task-based execution, the enqueuing of tasks isn’t necessarily the fastest one (taking in some cases slightly more than 10ms). But, on the other hand, the time spent between the execution of consecutive tasks is good: about 3µs. That is, if it has enough work, a task-based execution can scale up pretty well. There are ways to speed this up.

By comparison, the time to start threads (measured from the point where we start the threads until we see the task running in Tracy), can be 36ms.

In our examples the tasks did not do any locking; they were working in perfect isolation. If however there are locks between the tasks, then having more threads would amplify the negative effects of the locks. So, a task-based execution would be typically better than a thread-based execution.

Although not shown here, my personal experience with multiple threads running on the same core is the following: it’s faster to run two tasks in sequence on one core than to run them in parallel on the same core.

Also, one thing to notice that for a task-based execution, the scheduler knows how to distribute the tasks between the worker threads. This avoids the problem discussed in the static assignment section above.

Conclusions

This point was written to explain the difference between task and thread, and how an execution policy connects the two. Again, tasks are user-level independent work units, whereas threads are OS abstractions that allow us to execute tasks.

From a usability point of view, of course, the programmers should be more concerned about tasks and not that concerned about threads. By doing so, we raise the abstraction and let the programmers focus on solving the problem at hand.

From a performance point of view, we showed that a task-based execution policy has some advantages over a thread-based execution policy.

Therefore, one should avoid using threads directly, and instead, use tasks over a task-based concurrency framework.

Keep truthing in all your tasks!

Comments